- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Development of an action programme tackling obesity-related behaviours in adolescents: a participatory system dynamics approach

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 22, Article number: 30 (2024)

Abstract

System dynamics approaches are increasingly addressing the complexity of public health problems such as childhood overweight and obesity. These approaches often use system mapping methods, such as the construction of causal loop diagrams, to gain an understanding of the system of interest. However, there is limited practical guidance on how such a system understanding can inform the development of an action programme that can facilitate systems changes. The Lifestyle Innovations Based on Youth Knowledge and Experience (LIKE) programme combines system dynamics and participatory action research to improve obesity-related behaviours, including diet, physical activity, sleep and sedentary behaviour, in 10–14-year-old adolescents in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. This paper illustrates how we used a previously obtained understanding of the system of obesity-related behaviours in adolescents to develop an action programme to facilitate systems changes. A team of evaluation researchers guided interdisciplinary action-groups throughout the process of identifying mechanisms, applying the Intervention Level Framework to identify leverage points and arriving at action ideas with aligning theories of change. The LIKE action programme consisted of 8 mechanisms, 9 leverage points and 14 action ideas which targeted the system’s structure and function within multiple subsystems. This illustrates the feasibility of developing actions targeting higher system levels within the confines of a research project timeframe when sufficient and dedicated effort in this process is invested. Furthermore, the system dynamics action programme presented in this study contributes towards the development and implementation of public health programmes that aim to facilitate systems changes in practice.

Background

The high prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity [1] is considered a complex public health problem as it is driven by multiple, dynamic and interrelated factors, ranging from individual behaviours (e.g. daily sugar intake) to more upstream factors (e.g. urbanization). To address this complexity, systems approaches are increasingly being used in the development and implementation of public health programmes [2]. One such approach is system dynamics (SD), which possesses various characteristics, including programmes sensitive to starting conditions (context-specific); dynamic and adapting over time on the basis of new (system) insights; and developed through participatory processes [3, 4].

As SD approaches are sensitive to starting conditions and acknowledge that changes in initial conditions may influence programme effects, programmes should start with understanding the targeted system’s complexity [5]. In our case, this implies understanding how the current system contributes to childhood overweight and obesity prevalence. In public health research, this system understanding has mostly been operationalized through the development of causal loop diagrams (CLDs), which pose a visual representation of a system consisting of closed loops of causal influences. These CLDs are based on, for example, literature reviews, experts’ knowledge and group model building (GMB) workshops with the target group [6].

While CLDs are increasingly applied to demonstrate the complexity of public health problems, there are few examples of how such a system understanding can subsequently facilitate systems changes [6]. Systems changes can be facilitated by identifying and intervening on leverage points (LPs). LPs refer to places in the system where one can intervene to produce change across system parts and/or the system as a whole [7, 8]. Allegedly, the more LPs are targeted and the more diverse they are, the higher the chance of successfully facilitating systems changes [8]. A review on CLD development and application within public health found 12 out of 23 studies that identified LPs [6]. However, most studies only mentioned LPs as an aspirational next step to examine. Only three studies provided a more thorough description of LPs (concerning children’s environmental health [9], the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [10] and policies addressing obesity [11]). None of the studies specified how LPs informed action programme development.

In theory, following the above-mentioned SD principles, programmes should target numerous LPs at different system levels, including the higher system levels. According to the framework for systems change by Foster-Fishman and colleagues [5], programmes must target both the system structure (which includes factors, connections and feedback loops) and function (which determines the system behaviour) to alter the status quo. For example, a particular programme advocates that the purpose of supermarkets should not only be to maximize profit for their shareholders (the current system function), but also to contribute to ‘raising’ healthy adolescents (the new system function). Although several frameworks exist that help distinguish the different system levels [7, 12,13,14], to the best of our knowledge, no study within public health illustrates how a system understanding can help identify LPs that can subsequently inform action development and contribute towards achieving systems changes.

In this paper, we used the Lifestyle Innovations Based on Youth Knowledge and Experience (LIKE) programme as a case study to illustrate how a previously obtained understanding of the pre-existing system of obesity-related behaviours in adolescents [15] was used to identify LPs and subsequently develop an action programme within a SD approach to inform and facilitate systems changes.

Methods

The LIKE programme

LIKE is part of the Amsterdam Healthy Weight Programme (AHWP), a local-government-led whole systems approach with the long-term goal of reducing childhood overweight and obesity in Amsterdam, the Netherlands [16]. LIKE focuses on the transition from child to adolescent (ages 10–14) and is implemented in three ethnically diverse neighbourhoods with a lower socioeconomic position in the Amsterdam East district. LIKE uses a SD and participatory action research approach in developing, implementing and evaluating a dynamic action programme that can help change the current system towards one where healthy lifestyle behaviours are promoted [17]. The LIKE consortium is a transdisciplinary team consisting of academic researchers, policymakers at the city level and Amsterdam East district and professionals working for the AHWP.

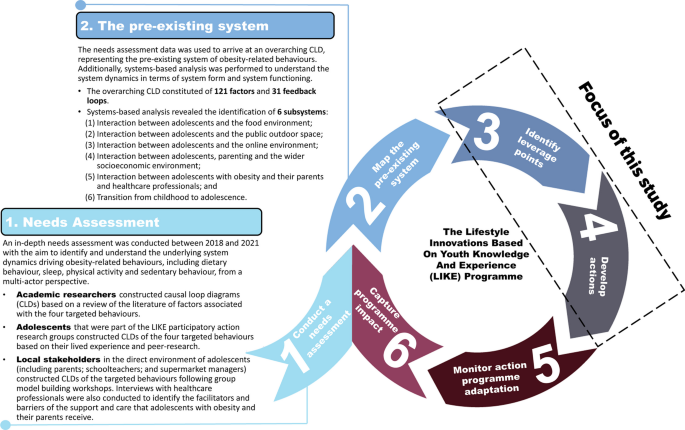

The LIKE programme centres around a six-stage cyclic process, including: (1) conduct a needs assessment; (2) map the pre-existing system; (3) identify LPs; (4) develop actions; (5) monitor action programme adaptation; and (6) capture programme impact (Fig. 1) [3]. Stages 1 and 2 took place between 2018 and 2021 and involved an in-depth mixed-methods needs assessment [17, 18]. This needs assessment captured an understanding of the underlying SD driving obesity-related behaviours from the perspective of multiple actors, including academic researchers, adolescents and local stakeholders, into a CLD. This CLD contained 121 factors and 31 feedback loops and consisted of six subsystems, including: (S1) interaction between adolescents and the food environment; (S2) interaction between adolescents and the public outdoor space; (S3) interaction between adolescents and the online environment; (S4) interaction between adolescents, parenting and the wider socioeconomic environment; (S5) interaction between adolescents with obesity and their parents and healthcare professionals; and (S6) transition from childhood to adolescence [15].

The current study builds on these system insights to develop a participatory SD action programme by identifying LPs (stage 3) that inform the development of actions (stage 4). In LIKE, adolescents and local stakeholders developed various action ideas using participatory action research (Emke et al., in preparation, 2024) and GMB (Waterlander et al., in preparation, 2024), respectively. In parallel, the LIKE consortium initiated additional action ideas by building on the insights gained from the action development process by adolescents and local stakeholders; targeting the functioning of the system; and conducting systems-based analysis. These consortium-initiated actions are the focus of the present paper.

Both stage 5 (monitor action programme adaptation) and stage 6 (capture programme impact) will be addressed elsewhere (de Pooter et al., in preparation, 2024; Luna Pinzon et al., in preparation, 2024). Furthermore, the current paper will not assess implementation, outputs and outcomes of the action programme. The remaining part of the methods section illustrates how the LIKE evaluation team (WW, ALP, NdP, KS) guided the LIKE consortium through a series of steps to identify LPs and develop action ideas. This study was approved by the institutional medical ethics committee of Amsterdam UMC, Location VUMC (2018.234).

Procedure for the identification of leverage points and development of action ideas

The evaluation team guided the LIKE consortium through six steps to identify LPs and subsequently develop action ideas. These steps are outlined below in more detail.

Step 1: identifying underlying mechanisms

Step 1 involved determining which SD within the pre-existing system the LIKE consortium aimed to target (first). In February 2020, the LIKE consortium discussed all the collected data as part of the needs assessment stage thus far, focusing on the produced CLDs supplemented with data from the participatory action research groups and an overview of actions already taking place in the Amsterdam East district. All this information was collectively discussed with the aim to identify and prioritize underlying mechanisms, that is, a segment of a larger process in the system (causes of the causes) [18, 19], by asking the question: Taking into account the needs assessment results, what are the most important mechanisms contributing to unhealthy lifestyles among adolescents aged 10–14? Mechanisms were prioritized by considering system boundaries, which define the system parts that are included or excluded for this particular analysis [3]. These boundaries related to, for example, the focus on the transition period from childhood to adolescence and Amsterdam East as the setting.

Step 2: action-groups formation

In step 2, the LIKE consortium split up into groups to work on the identified mechanisms. Participants could join one or multiple groups on the basis of their expertise and/or interest. This resulted in the formation of five action-groups. A prerequisite was for each group to include at least two academic researchers, one professional working for the AHWP and one policymaker working for the municipality. Action-groups were encouraged to meet regularly to discuss their plan of action and plenary meetings with all action-groups were organized by the evaluation team every 6 weeks to discuss progress.

Step 3: further refinement of the identified mechanisms

In step 3, the evaluation team guided action-groups in understanding the targeted mechanisms from an SD perspective. Each group received an action-group workbook [see Additional file 1] with different sections to complete. These sections included: a description of the mechanism based on academic literature; an assessment of why the mechanism was relevant to the transition from child to adolescent; and an assessment about why the mechanism was particularly relevant at this moment (in comparison with, for example, 20 years ago). Action-groups were also encouraged to consult external experts to further refine their mechanisms.

Step 4: identification of leverage points and system levels analysis

Step 4 aimed to identify LPs that would help disrupt the identified mechanisms. To achieve this, we conducted systems-level analysis by applying the Intervention Level Framework (ILF). The ILF was developed by Johnston and colleagues to assist in finding solutions to complex health problems [13]. The ILF consists of five system levels and intervening at the higher levels will produce the most disruptive systems changes. The highest ILF level is a system’s paradigm, representing its deepest-held belief. Level two, the system, together with the system paradigm, dictates the way in which the system behaves and determines which system outcomes are produced. Level three is the system structure and defines the interconnections between the different system parts. Level four describes the system’s feedback and delays. This level refers to a system’s ability for self-regulation by supplying information about outcomes of actions back to the source of those actions. Lastly, level five describes the structural elements of a system in terms of actors or physical elements [13].

The action-groups used a table explaining the ILF levels and conducted ILF analysis. This analysis involved the identification of LPs for their mechanisms and the assignment of one of the five ILF levels to each LP. To facilitate this, action-groups used guiding questions, such as those described in the Action Scales Model [14]. For example, the following question helped in identifying a LP at the system paradigm level: What are the prevailing assumptions, beliefs and values that explain why things are done as they are? [14] LPs and their corresponding ILF levels were included in the action-group’s workbook [see Additional file 1].

Step 5: generating action ideas

In step five, action-groups generated action ideas on the basis of the identified LPs. At the action idea level, it was important for groups not to focus on the specific form of the action (e.g. a workshop) but to specify a theory of change in terms of the action function [3]. In other words, the theory of change specified how the particular action would target the identified LP, thereby contributing to disrupting the targeted mechanism and thus ultimately aiding in achieving the desired systems changes. To facilitate this, action-groups answered the question: Which actions can help target the LP and ultimately aid in achieving systems changes (define action idea in terms of action function and using the S.M.A.R.T criteria [20])? Action ideas were added to the action-group’s workbook [see Additional file 1] and included these characteristics: targeted mechanism and LP, system level (ILF level), action name, action form and action theory of change.

Step 6: assessing the degree to which action ideas could be embedded in existing initiatives

In step six, action-groups investigated which actions were already happening in the LIKE focus area to determine the degree to which action ideas could be embedded in existing initiatives. Action-group members working for the AHWP and municipality provided this information. Lastly, action-groups were encouraged to involve external stakeholders to aid in the further development of the action ideas.

Reflection, adaptation and monitoring

Action development continuously occurred in a cyclic process, wherein ideas were adapted on the basis of the context and setting in which they ought to be implemented, as well as the feedback received from the evaluation team. For example, during action development, if it became apparent that an action idea was not feasible due to a lack of alignment with existing initiatives or redundancy, the idea was either adapted or abandoned. Similarly, efforts to emphasize actions at specific system levels were adjusted over time. For instance, the focus on targeting higher system levels was increased when we observed a shortage of action ideas at those levels. The evaluation team supported action-groups in applying systems thinking throughout the action programme development process via developed workbooks (see Additional file 1), the use of guiding questions and by organizing plenary meetings. To track the progress of the action programme, a monitoring system was set up, composed of: action-group’s workbooks; action register database containing, for example, name, action form and function; and stakeholder database containing the type of stakeholders involved.

Data sources and analysis

For data analysis, the lead researcher (ALP) read and summarized all action-group workbooks and extracted action ideas generated by the LIKE consortium from the action register database. A second researcher (NdP) supported this process. Note that action-groups generated various action ideas throughout the process, and that not all actions were actually executed or specified into detailed action plans. This paper focuses on all actions for which action-groups provided specified theories of change. Identified mechanisms, targeted LPs and corresponding action ideas were ordered per subsystem. The evaluation team discussed preliminary findings to ensure that these reflected the process followed within the LIKE programme.

Results

Five of the six previously identified subsystems (stages 1 and 2 [15]) were targeted by the action-groups. These included: food environment, public outdoor spaces, socioeconomic environment, healthcare and transition from child to adolescent. No LPs specifically targeted subsystem 3, describing the interaction between adolescents and the online environment as action-groups prioritized the other subsystems. The remaining part of this section does not discuss this subsystem.

Within the five targeted subsystems, action-groups initially identified 12 mechanisms. After prioritizing, we selected eight mechanisms to further identify LPs and subsequently develop action ideas. These final mechanisms included: (M1) power dynamics in the current food system; (M2) the use of public outdoor spaces for physical activity by adolescents; (M3) the role of parents during adolescence; (M4) livelihood security and poverty; (M5) connection between health ambassadors (volunteers), municipality and community organizations; (M6) match between local health promotion activities and parents’ needs; (M7) match between obesity healthcare services and the needs of adolescents with obesity and their parents; and (M8) social norms influencing health behaviours in adolescents. Within these mechanisms, action-groups initially defined a wide range of potential LPs at each of the ILF levels. After refinement, action-groups made a final selection of 9 LPs, from which they developed a total of 14 action ideas. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of how these action ideas were divided across the LPs and which of the five ILF system levels these LPs targeted (referred to as LP1–LP9 in Fig. 2). We describe these results per subsystem below.

Subsystem 1 regarding the interaction between adolescents and the food environment: mechanisms, leverage points and action ideas

A total of one mechanism and two leverage points were identified and four action ideas developed within subsystem 1 (Table 1). M1 refers to the power dynamics that exist between local food retailers that want to offer healthier food products and large global food companies selling unhealthy food products for attractive profits. To arrive at the final LPs selection, action groups used two guiding questions: Who are the key decision-makers in shaping the local food environment for adolescents? and, Given our established networks within the local and national food system, how can we use our sphere of influence to make the Amsterdam food system healthier?

The first guiding question resulted in the identification of supermarkets as one of the most important players in shaping the food environment. ILF analysis revealed that, ultimately, changes in system goals would be needed to create healthier supermarkets. Otherwise, the system reverts to generating solely financial profits (LP1). A1 (GMB workshops) therefore aimed to change the beliefs of local supermarkets by involving them in GMB workshops. During these workshops, supermarkets would analyse the food system, thereby highlighting their role in shaping it.

The second guiding question identified the food policy context (national and local) as an important factor to influence (LP2). Hence, A2 (exposing retails tactics and lack of action) aimed to generate local evidence about the need for top-down measures from the government. A3 (active lobbying initiative) and A4 (entrepreneur network) focussed on improving and maintaining the collaboration between academia and the municipality. Their goal was to exchange knowledge and information, thereby contributing to a shared agenda.

Subsystem 2 regarding the interaction between adolescents and the public outdoor space: mechanisms, leverage points and action ideas

One mechanism and one leverage point were identified and one action idea developed that targeted subsystem 2 (Table 2). M2 outlines how the increasing density in cities such as Amsterdam has resulted in limited public outdoor spaces for active play and sports, as well as unattractive spaces for adolescents. Moreover, although citizen participation is gaining popularity, participation of adolescents in the design of public outdoor spaces is not yet common in policy practice. ILF analysis revealed that to disrupt M2, a new system goal was required, prioritizing the redesign of public outdoor spaces in co-creation with adolescents. The goal is to make these spaces more attractive, especially for active play and sport (LP3).

The guiding question used was: How can we use our experience with co-creation to alter the public outdoor space in such a way that adolescents make more and active use of it? A5 (co-creation outdoor space) therefore aimed to organize a co-creation process wherein adolescents, the municipality and community organizations participated in redesigning a designated outdoor space close to a local school. The insights gained could then serve as a lever to advocate for the inclusion of adolescents in the future design of public outdoor spaces.

Subsystem 4 regarding the interaction between adolescents, parenting and the wider socioeconomic environment: mechanisms, leverage points and action ideas

A total of four mechanisms and four leverage points were identified and four action ideas developed that targeted subsystem 4 (Table 3).

In the transition from child to adolescent, parents undergo a new role from a more managerial to a more coaching role of their children (M3). Parents might therefore find it difficult to set, monitor and enforce rules regarding healthy behaviours (LP4). The guiding question used was: Which initiatives already exist that reach parents and can help improve parental skills? This resulted in the identification of a programme within the AHWP, where parents take the role of health ambassadors to stimulate fellow parents to encourage a healthier lifestyle in their children. A6 (Rules Rule) aimed to educate health ambassadors about parenting skills so that they can further spread this knowledge with other parents in the community.

Subsystem 4 further relates to households living in relative poverty in Amsterdam East, whereby financial and social problems may accumulate, resulting in higher stress levels and less attention for creating and sustaining healthy behaviours amongst parents (M4). ILF analysis revealed that a new system goal was needed in which parents would no longer be forced to prioritize household livelihood security at the expense of stimulating healthy behaviours (LP5). The guiding question used was: Which municipal policy systems have overlapping goals and to what extent can these be aligned? This resulted in A7 (connecting health and livelihood security), which aims to investigate how the municipality can avoid working in silos and integrate the three policy areas of household income, housing and health.

The last two mechanisms identified relate to common misunderstandings between professionals and parents in the work of the health ambassadors (M5) and in the local health promotion activities offered to parents (M6). ILF analysis revealed that health ambassadors do not feel supported in their work, which negatively influences their commitment (LP6). A8 (interviews with health ambassadors) therefore focuses on addressing this perceived lack of support. ILF analysis further revealed that current health promotion activities do not match the expectations and needs of parents (LP7). A9 (parenting debates) thus aims to gain a better understanding of which factors contribute towards matching the needs of parents so that these insights can be disseminated to other activities.

Subsystem 5 regarding the interaction between adolescents with obesity and their parents and healthcare professionals: mechanisms, leverage points and action ideas

One mechanism and one leverage point were identified, and three action ideas developed that targeted subsystem 5 (Table 4). Mechanism 7 describes that the working methods, organization and competences of healthcare professionals do not sufficiently fit the needs of adolescents with obesity and their parents. The national model for integrated care for childhood overweight and obesity [21,22,23] encourages healthcare professionals to take the complexity embedded in factors related to childhood obesity into account in the support and care systems. However, there are barriers in the implementation of the model, for example, a lack of time and resources within the current healthcare system, and the need to invest in a strong family–professional relationship [24, 25].

ILF analyses indicated that to help disrupt M7, the support and care families receive from healthcare professionals needed intensifying (LP8). A10–12 therefore aim to help tailor the childhood obesity support and care to the needs of adolescents with obesity and their parents with the goal of empowering families to achieve a healthier lifestyle.

Subsystem 6 regarding the transition from childhood to adolescence: mechanisms, leverage points and action ideas

One mechanism and one leverage point were identified and two action ideas developed that targeted subsystem 6 (Table 5). M8 describes how adolescents consider unhealthy behaviours normal and cool as part of the social norm. As adolescents seek acceptance from their peers, they will, therefore, not deliberately deviate from this social norm.

ILF analysis revealed that to help disrupt M8, the social norm of exhibiting unhealthy behaviours (especially when hanging out with peers) needed to be altered (LP9). One way to initiate this shift in belief is by using role models to encourage adolescents to start exhibiting healthier behaviours. A13 (peer role models) and A14 (role models network) aim to use peers and youth workers as agents for changing the unhealthy social norm (A13–A14).

Discussion

Principal findings

This study presents the outline of an action programme tackling obesity-related behaviours in the transition period from childhood to adolescence (ages 10–14) within an SD approach. We developed the action programme by translating a previously obtained system understanding into mechanisms and subsequently identifying LPs and developing action ideas that can contribute towards achieving system changes. Interdisciplinary action-groups were formed, which were actively guided in applying systems thinking throughout the development process. The resulting action programme focussed on 8 mechanisms using 9 LPs and 14 action ideas with aligning theories of change targeting both the system’s structure and function. This paper thereby illustrates the feasibility of formulating actions targeting higher system levels within the confines of a research project timeframe when sufficient and dedicated effort is put into this process.

Comparison with the development of other system approaches

Substantial heterogeneity exists in public health programmes that take a system’s approach in terms of design, implementation and outcomes produced [2]. Within public health, GMB is the most commonly used method to gain system understanding and/or inform the development of actions [6]. In the context of childhood overweight and obesity prevention, most examples on the use of GMB to develop actions can be found in programmes conducted in Australia [26,27,28].

One such example is the Whole of Systems Trial of Prevention Strategies for Childhood Obesity conducted in Victoria, Australia [26]. In this programme, a system understanding was developed by combining anthropometric and local behavioural data with CLDs produced in GMB sessions with community members. From these sessions, an action programme with more than 400 actions was created. Unfortunately, details of the process following the move from system understanding to a SD action programme are lacking. The authors do mention that a similar framework to the ILF was applied (Foster-Fishman’s framework for transformative systems change [5]) to retrospectively gain insights into the system levels that actions were targeting. However, the application of this framework was conducted independently from the action development process by the communities [29]. Details about how SD actions were constructed prospectively are important because it can help guide other programmes taking a SD approach.

Another study also used community GMB workshops to identify systemic barriers to fruit and vegetable intake in children in New Zealand [30]. Study participants developed actions by taking into account LPs and answering three questions: What variables (of the CLD) could you increase or decrease?; How could you impact connections: strengthen, or weaken a connection, speed it up or slow it down, add or delete connections?; and How could you impact the ‘rules’ that govern the system or the goals that it is trying to achieve? [31]. This resulted in 18 actions that targeted four subsystems, including the home environment, fast food, community nutrition and health outcomes. The authors, however, concluded that participants were unable to generate specific action ideas that took into account the higher system levels and instead reverted to traditional, individual-focused actions. They also concluded that this was likely due to insufficient time being allocated for this process [30]. However, it could also be the case that guiding questions alone do not sufficiently aid in arriving at the higher system levels and that the application of a framework, such as the ILF, is also needed. In LIKE, we tried to overcome these issues by guiding action-groups in the whole process from system understanding to action development. Furthermore, we allocated sufficient time and guidance for groups to familiarize themselves with the concept of applying the ILF to identify LPs through practical exercises and to allow actions to adapt over time as system insights increased.

Reflections on the methods followed to identify leverage points and develop action ideas

In SD approaches, it is crucial to develop an a priori system understanding because this serves as the starting point to identify LPs and develop actions. In addition, it is crucial that this system understanding is shared among stakeholders who are involved in the development of actions and who may not necessarily be involved in the previous phases. This shared understanding will contribute to developing a shared vision of what the programme aims to achieve and thereby help promote ownership of the problem and potential solutions [5]. SD approaches are typically formed by transdisciplinary teams who work together to understand and change the targeted system [32,33,34]. However, the challenges associated with how such teams are expected to work in practice are underreported [34]. The LIKE consortium included representatives from academia, policy and practice. To promote cohesive teamwork, a shared vision, trust and commitment within the project, substantial efforts were made throughout the duration of LIKE. These efforts included, amongst other things, regular meetings (four times per year) of the LIKE consortium to determine, for instance, the content of the action programme being developed and a workshop focused on clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the different LIKE members. Further details about the process of collaborating with different system actors when developing and implementing a SD action programme will be described elsewhere (Luna Pinzon et al., in preparation, 2024).

One way to support the identification of LPs beyond the qualitative process described in this paper is with the use of quantitative SD models. These models can explore potential futures and ask ‘what if’ questions [7]. In the context of the LIKE programme, this would entail translating the pre-existing CLD of obesity-related behaviours into a SD model, for example, using the methodology described in Crielaard et al., 2022 [35]. Next, it can, for example, be tested whether LP X would be a more promising lever to change the system instead of LP Y. On the basis of these ‘what if’ scenarios, a selection can be made as to which LPs to focus on. However, these models require data that can represent the factors included in the CLD, which we do not have access to in LIKE. Results from the wider LIKE evaluation could possibly be used to develop these models in the future.

The application of the ILF in this study was challenging due to its theoretical nature and the requirement of expertise on systems thinking [13, 14]. We tried to overcome this challenge by establishing an evaluation team that supported action-groups throughout the process with workbooks, using guiding questions and organizing plenary meetings. Recently, other frameworks to identify LPs have been developed, in addition to the ILF. First, Nobles et al. [14] developed the Action Scales Model, which also expands upon Meadows’ original 12 places to intervene in a system [7]. At the time LPs were identified in LIKE, the Action Scales Model had not yet been developed and therefore only the guiding questions of the action scales model to identify LPs were used in this study to supplement our ILF procedure. Another recently developed alternative to the ILF is the Public Health 12 framework [12]. This framework offers a translation of Meadows’ original 12 levels into a language that is practical and enables the operationalization of systems changes within public health [12]. On the basis of the challenges we faced in LIKE with the application of the five broader levels of the ILF, we believe that the application of the Public Health 12 framework will only be possible once enough experience is gathered in correctly distinguishing each system level and understanding its corresponding LPs.

In this paper, we departed from a more ‘traditional’ view of public health prevention programmes or interventions as a ‘standardized package of actions’. Instead, we applied a SD perspective and arrived at a ‘SD action programme’. An important characteristic of such a SD action programme is that actions are not only defined in terms of their form, but also in terms of their function by making their theories of change explicit. Furthermore, by consciously differentiating and considering whether LPs and actions target the structural (lower) system levels or the more functional (higher) system levels, we found that we were gradually able to formulate actions targeting the higher system levels. Although we acknowledge that instigating ‘genuine’ changes in systems paradigms or goals requires more time than a typical research project allows, this paper illustrates the feasibility of formulating actions targeting higher system levels within the confines of a research project timeframe when sufficient and dedicated effort is put into this process.

An important prerequisite to note here is a certain level of flexibility amongst all stakeholders involved due to the dynamics nature of a systems approach. For example, as insights of the system emerge over time, actions would need to be potentially adapted or abandoned [3]. The challenges arising from this dynamic process (de Pooter et al., in preparation, 2024) as well as lessons learned from the process of implementing a system dynamics project into a real-life setting (Luna Pinzon et al., in preparation, 2024), will be thoroughly analysed in separate articles. This includes the importance of trust among project members that is needed to deal with the dynamic character of the programme, as well as the importance of combining expertise in systems thinking with an understanding of the context and environment in which these actions are implemented.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that presents the development of a SD action programme informed by a previously obtained systems understanding and targeting multiple system levels. Furthermore, this study illustrates how LPs can be identified prospectively and how these can inform the development of actions that facilitate systems changes. This study brings important findings as to what an action programme within a SD approach could look like and how this differs from more traditional public health interventions. Nevertheless, while promising, our study does not provide evidence on the effectiveness of this action programme in terms of concrete system outcomes. Changing a system is a participatory process that can take up to several years and these types of evaluation questions will be answered in future studies.

In terms of the action development process, we initially aimed to develop a programme that was dynamic and could be adapted on the basis of the new insights that emerged from the system [3, 36]. Although this was achieved to some extent (details of the LIKE action programme adaptation will be described elsewhere), not all of this was possible because of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns. This resulted in a loss of momentum for some of the action-groups, and online instead of physical meetings and information gathering.

Lastly, the results presented in this study constitute only a part of the LIKE action programme. The LIKE action programme is composed of a wider collection of mechanisms, LPs and actions which are developed using participatory action research with adolescents and GMB sessions with stakeholders. The results from these participatory processes will be described in detail elsewhere (de Pooter et al., in preparation, 2024).

Conclusions

This study provides details on the development of a SD action programme targeting obesity-related behaviours in adolescents. Interdisciplinary action-groups were supported in the identification of system’s mechanisms and the application of the ILF to identify LPs targeting system structure and function. The results show how such a SD action programme differs from traditional public health interventions. This is achieved by describing action ideas in terms of function, theories of change and the system levels they are targeting, thereby demonstrating the feasibility of developing actions targeting higher system levels within the constraints of a research project timeframe. We believe these insights can contribute to the further development and implementation of SD approaches within public health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.

Abbreviations

- SD:

-

System dynamics

- CLD:

-

Causal loop diagram

- GMB:

-

Group model building

- LPs:

-

Leverage points

- ILF:

-

Intervention level framework

References

World Health Organization. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2022.

Bagnall A-M, Radley D, Jones R, Gately P, Nobles J, Van Dijk M, et al. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–14.

Luna Pinzon A, Stronks K, Dijkstra C, Renders C, Altenburg T, den Hertog K, et al. The ENCOMPASS framework: a practical guide for the evaluation of public health programmes in complex adaptive systems. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022;19(1):1–17.

Patton MQ. Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. p. 375.

Foster-Fishman PG, Nowell B, Yang H. Putting the system back into systems change: a framework for understanding and changing organizational and community systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39(3–4):197–215.

Littlejohns LB, Hill C, Neudorf C. Diverse approaches to creating and using causal loop diagrams in public health research: recommendations from a scoping review. Public Health Reviews (2107–6952). 2021;42.

Meadows D, Wright D. Thinking in systems: a primer. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing; 2008.

Foster-Fishman PG, Behrens TR. Systems change reborn: rethinking our theories, methods, and efforts in human services reform and community-based change. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39(3–4):191–6.

Brereton CF, Jagals P. Applications of systems science to understand and manage multiple influences within children’s environmental health in least developed countries: a causal loop diagram approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3010.

Sahin O, Salim H, Suprun E, Richards R, MacAskill S, Heilgeist S, et al. Developing a preliminary causal loop diagram for understanding the wicked complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic. Systems. 2020;8(2):20.

Clarke B, Kwon J, Swinburn B, Sacks G. Understanding the dynamics of obesity prevention policy decision-making using a systems perspective: a case study of Healthy Together Victoria. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1): e0245535.

Bolton KA, Whelan J, Fraser P, Bell C, Allender S, Brown AD. The Public Health 12 framework: interpreting the ‘Meadows 12 places to act in a system’ for use in public health. Arch Public Health. 2022;80(1):1–8.

Johnston LM, Matteson CL, Finegood DT. Systems science and obesity policy: a novel framework for analyzing and rethinking population-level planning. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1270–8.

Nobles JD, Radley D, Mytton OT, team WSOp. The Action Scales Model: a conceptual tool to identify key points for action within complex adaptive systems. Perspect Public Health. 2021:17579139211006747.

Luna Pinzon A, Stronks K, Emke H, van den Eynde E, Altenburg T, Dijkstra SC, et al. Understanding the system dynamics of obesity-related behaviours in 10- to 14-year-old adolescents in Amsterdam from a multi-actor perspective. Front Public Health. 2023;11.

Sawyer A, den Hertog K, Verhoeff AP, Busch V, Stronks K. Developing the logic framework underpinning a whole-systems approach to childhood overweight and obesity prevention: Amsterdam Healthy Weight Approach. Obes Sci Pract. 2021;7:591.

Waterlander WE, Luna Pinzon A, Verhoeff A, Den Hertog K, Altenburg T, Dijkstra C, et al. A system dynamics and participatory action research approach to promote healthy living and a healthy weight among 10–14-year-old adolescents in Amsterdam: the LIKE programme. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4928.

Waterlander WE, Singh A, Altenburg T, Dijkstra C, Luna Pinzon A, Anselma M, et al. Understanding obesity-related behaviors in youth from a systems dynamics perspective: the use of causal loop diagrams. Obes Rev. 2021;22(7): e13185.

Rod MH, Rod NH, Russo F, Klinker CD, Reis R, Stronks K. Promoting the health of vulnerable populations: three steps towards a systems-based re-orientation of public health intervention research. Health Place. 2023;80: 102984.

Doran GT. There’s a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manage Rev. 1981;70(11):35–6.

Halberstadt J, Sijben M. Summary National model Integrated care for childhood overweight and obesity. 2019.

Sijben M, van der Velde M, van Mil E, Stroo J, Halberstadt J. Landelijk model-Ketenaanpak voor kinderen met overgewicht en obesitas. 2018.

Halberstadt J, Koetsier LW, Sijben M, Stroo J, van der Velde M, van Mil EGAH, Seidell JC. The development of the Dutch “National model integrated care for childhood overweight and obesity.” BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):359.

de Pooter N, van den Eynde E, Raat H, Seidell JC, van den Akker EL, Halberstadt J. Perspectives of healthcare professionals on facilitators, barriers and needs in children with obesity and their parents in achieving a healthier lifestyle. PEC Innov. 2022;1:100074.

Koetsier L, Van Mil M, Eilander M, van den Eynde E, Baan CA, Seidell J, Halberstadt J. Conducting a psychosocial and lifestyle assessment as part of an integrated care approach for childhood obesity: experiences, needs and wishes of Dutch healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–11.

Allender S, Millar L, Hovmand P, Bell C, Moodie M, Carter R, et al. Whole of systems trial of prevention strategies for childhood obesity: WHO STOPS childhood obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(11):1143.

Maitland N, Williams M, Jalaludin B, Allender S, Strugnell C, Brown A, et al. Campbelltown–changing our future: study protocol for a whole of system approach to childhood obesity in South Western Sydney. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–9.

O’Halloran S, Hayward J, Strugnell C, Felmingham T, Poorter J, Kilpatrick S, et al. Building capacity for the use of systems science to support local government public health planning: a case study of the VicHealth Local Government Partnership in Victoria, Australia. BMJ Open. 2022;12(12): e068190.

Allender S, Brown AD, Bolton KA, Fraser P, Lowe J, Hovmand P. Translating systems thinking into practice for community action on childhood obesity. Obes Rev. 2019;20:179–84.

Gerritsen S, Renker-Darby A, Harré S, Rees D, Raroa DA, Eickstaedt M, et al. Improving low fruit and vegetable intake in children: findings from a system dynamics, community group model building study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8): e0221107.

Gerritsen S, Harré S, Rees D, Renker-Darby A, Bartos AE, Waterlander WE, Swinburn B. Community group model building as a method for engaging participants and mobilising action in public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3457.

Appel JM, Fullerton K, Hennessy E, Korn AR, Tovar A, Allender S, et al. Design and methods of Shape Up Under 5: integration of systems science and community-engaged research to prevent early childhood obesity. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8): e0220169.

Garcia LM, Hunter RF, de la Haye K, Economos CD, King AC. An action‐oriented framework for systems‐based solutions aimed at childhood obesity prevention in US Latinx and Latin American populations. Obes Rev. 2021:e13241.

Such E, Smith K, Woods HB, Meier P. Governance of intersectoral collaborations for population health and to reduce health inequalities in high-income countries: a complexity-informed systematic review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(12):2780.

Crielaard L, Uleman JF, Châtel BD, Epskamp S, Sloot P, Quax R. Refining the causal loop diagram: a tutorial for maximizing the contribution of domain expertise in computational system dynamics modeling. Psychol Methods. 2022.

McGill E, Er V, Penney T, Egan M, White M, Meier P, et al. Evaluation of public health interventions from a complex systems perspective: a research methods review. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113697.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mary Nicolaou for reading and reviewing an earlier draft of this manuscript. We would also like to thank all LIKE consortium members who participated in the action development process.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative: an initiative with support of the Dutch Heart Foundation, ZonMw, CVON2016-07 LIKE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ALP, WW and KS were responsible for conception and design of the work; WW and KS for supervision; KS, AV, MC, WN and CR for funding acquisition; ALP, WW and KS for writing – original draft; and ALP, WW, NdP, TA, CD, HE, EvdE, MO, VB, CR, JH, WN, KdH, MC, AV and KS for interpretation and critically reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the data collections was obtained from the institutional medical ethics committee of Amsterdam UMC, Location VUMC (2018.234). Consent to participate in this study was provided by participants.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication of data was obtained from all study participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Action-group workbook template. The additional table includes the template of the workbook used by action groups in the LIKE programme to identify leverage points and develop action ideas.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Luna Pinzon, A., Waterlander, W., de Pooter, N. et al. Development of an action programme tackling obesity-related behaviours in adolescents: a participatory system dynamics approach. Health Res Policy Sys 22, 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-024-01116-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-024-01116-8